7.30.2005

apichatpong weerasethakul's tropical malady

i can't get tropical malady out of my head. it's been over a week since i've seen it, and i'm beginning to debate spending ten bucks to see it again when it opens here in philly. i'll attempt to explain why...

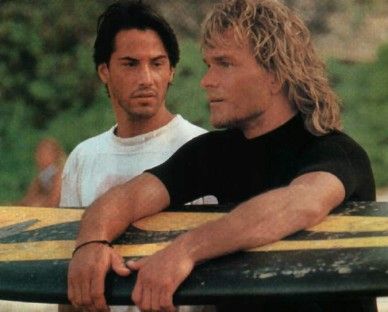

malady is told in two parts, which-- though stylistically quite distinct-- feed off one another in a circular sort of way. it begins with a slow-going gay love story involving a soldier and an elusive young man from a country town. following an essentially plotless (and strangely utopian) love affair, the couple eventually depart and the second act begins. here, the same two actors appear and keng, the soldier, appears to be playing the same role (?). the "second" narrative concerns a thai myth about a spirit inhabiting a jungle with the ability to transform into a tiger. keng enters the jungle to find the spirit-- which is (inexplicably) played by the same actor (sakda kaewbuadee) as the country boy in the first narrative.

for starters, i can't honestly think of a film with less conflict than tropical malady. its slow, naturalistic style bears similarities to the work of other contemporary asian filmmakers (hou hsiao-hsien, tsai ming-liang wong kar-wai, etc.), but contains none of the wistful blueness that activates such films. the first half of malady might be described as a very realistic fairly tale. the two men meet, fall in love, and spend its duration very casually enjoying one another's company. it is punctuated by occasional markings of slight artifice-- a cheesy bit of dialogue, a canned smile that lasts too long, etc. and yet, no snarky distance accompanies such details. the artifice might best be described as magnetic-- in that it reverses its conventional logic and makes the film experience more intimate. its meaning amplifies within its occasional fabrications, and the awkward fit deepens its strange, expansive trance. malady is a film that takes desire very seriously, but does so with an extreme reverence for the lightness of such a feeling. there is no blockage to its desire, and if the characters go unfulfilled (as one might argue they do at the end of the first segment) it is by way of their desire itself. this ever present sensation glides along its course throughout the film with a stubborn and enigmatic optimism that has to be seen to be properly believed.

the second half makes an initial rupture from the first, and merits comparisons to several canonical heavy-hitters (apocalypse now, tarkovsky's stalker, 2001:a a space odyssey, etc.). keng enters the jungle with all the fear and trembling accompanying a great quest. he finds tong naked and tattooed, ripe and ready for all sorts of animal/man archetypal explanations. i know zero about thai mythology, and am undoubtedly missing a very layered contextual dimension of the film here. but still-- and this might just be my western sense of entitlement speaking-- it doesn't seem to matter much, in the end. as keng and tong wrestle and stumble and transform one another, the experience generates a sense of engagement too visceral and emotional to refer back to allegorical justifications. the structure is different, but the sweetness and humility of its initial hour remains. which isn't to say that one isn't given much to think about. instead, for me, its meaning is bound up within the sense of transformation (be it literal, spiritual, emotional, or--most importantly-- spectatorial transformation). the point is not to scrutinize the couple's regression/exaltation, but to experience the very climate of that transformation. malady's jungle has a bit of the crowded magic of henri rousseau's landscapes-- a similar twilight wonder appears (minus the nineteenth-century western exoticism). it is the sort of space that reduces you to a kid at a campfire, eagerly and fearfully ready to believe in whatever magic might arise.

but tropical malady bears no monsters. it is a love story to rival the best of them, and its conclusion moves in the same direction as its introduction. too often, philosophically, desire is formulated as the enemy. it traditionally occupies the lower tier of human existence, in the shadow of such unlikely bedfellows as salvation, justice and transcendental aesthetics. in a sense, malady gives desire its moment in the clouds. its gentle force is both question and answer, inhabiting both the corporeal and psychological make-up of its beneficiaries, suggesting-- with great lightness and profoundity-- that one simply notice its presence, in all its profundity.

malady is told in two parts, which-- though stylistically quite distinct-- feed off one another in a circular sort of way. it begins with a slow-going gay love story involving a soldier and an elusive young man from a country town. following an essentially plotless (and strangely utopian) love affair, the couple eventually depart and the second act begins. here, the same two actors appear and keng, the soldier, appears to be playing the same role (?). the "second" narrative concerns a thai myth about a spirit inhabiting a jungle with the ability to transform into a tiger. keng enters the jungle to find the spirit-- which is (inexplicably) played by the same actor (sakda kaewbuadee) as the country boy in the first narrative.

for starters, i can't honestly think of a film with less conflict than tropical malady. its slow, naturalistic style bears similarities to the work of other contemporary asian filmmakers (hou hsiao-hsien, tsai ming-liang wong kar-wai, etc.), but contains none of the wistful blueness that activates such films. the first half of malady might be described as a very realistic fairly tale. the two men meet, fall in love, and spend its duration very casually enjoying one another's company. it is punctuated by occasional markings of slight artifice-- a cheesy bit of dialogue, a canned smile that lasts too long, etc. and yet, no snarky distance accompanies such details. the artifice might best be described as magnetic-- in that it reverses its conventional logic and makes the film experience more intimate. its meaning amplifies within its occasional fabrications, and the awkward fit deepens its strange, expansive trance. malady is a film that takes desire very seriously, but does so with an extreme reverence for the lightness of such a feeling. there is no blockage to its desire, and if the characters go unfulfilled (as one might argue they do at the end of the first segment) it is by way of their desire itself. this ever present sensation glides along its course throughout the film with a stubborn and enigmatic optimism that has to be seen to be properly believed.

the second half makes an initial rupture from the first, and merits comparisons to several canonical heavy-hitters (apocalypse now, tarkovsky's stalker, 2001:a a space odyssey, etc.). keng enters the jungle with all the fear and trembling accompanying a great quest. he finds tong naked and tattooed, ripe and ready for all sorts of animal/man archetypal explanations. i know zero about thai mythology, and am undoubtedly missing a very layered contextual dimension of the film here. but still-- and this might just be my western sense of entitlement speaking-- it doesn't seem to matter much, in the end. as keng and tong wrestle and stumble and transform one another, the experience generates a sense of engagement too visceral and emotional to refer back to allegorical justifications. the structure is different, but the sweetness and humility of its initial hour remains. which isn't to say that one isn't given much to think about. instead, for me, its meaning is bound up within the sense of transformation (be it literal, spiritual, emotional, or--most importantly-- spectatorial transformation). the point is not to scrutinize the couple's regression/exaltation, but to experience the very climate of that transformation. malady's jungle has a bit of the crowded magic of henri rousseau's landscapes-- a similar twilight wonder appears (minus the nineteenth-century western exoticism). it is the sort of space that reduces you to a kid at a campfire, eagerly and fearfully ready to believe in whatever magic might arise.

but tropical malady bears no monsters. it is a love story to rival the best of them, and its conclusion moves in the same direction as its introduction. too often, philosophically, desire is formulated as the enemy. it traditionally occupies the lower tier of human existence, in the shadow of such unlikely bedfellows as salvation, justice and transcendental aesthetics. in a sense, malady gives desire its moment in the clouds. its gentle force is both question and answer, inhabiting both the corporeal and psychological make-up of its beneficiaries, suggesting-- with great lightness and profoundity-- that one simply notice its presence, in all its profundity.

kafka-like

i've spent the past month or so dealing with kafka-- i finally read the castle from cover to cover, followed by walter benjamin's famous essay on him, and ending with deleuze and guattari's toward a minor literature. during that time, i've been trying to formulate my own investment in his work.

as far as my personal inclinations go, like deleuze and guattari, i'm not terribly drawn to either of the two dominant approaches to him-- namely the spiritual and psychoanalytic routes. both have their merits as systems of interpretation, but i don't respond to them personally. the thought of a godless world excites me more than it startles me, and, uh, i guess i get along with my dad pretty well too. while the notion of a "minor" literature-- "to be a sort of stranger within (one's) own language"-- is a fascinating one, i find it less applicable to kafka than d & g might have one believe. "deleuzian" kafka is too covered in "deleuzian" fingerprints to amount to a convincing argument. at times, d & g seem more interested in themselves.

for me, it is through relationships, rather than bureaucracies, that kafka's k. begins to make sense. an example: a few years ago, me and a good friend were both emerging from troubled romantic relationships. sharing a sense of abandonment (or whatever) we began discussing one of the more abject moments of any break-up-- a demand, more or less, to be put on trial. you know the drill... a sense of rejection sets in, and one is filled with an otherworldly desire to know what is wrong with one's self. an embarrassing plea to be told inevitably follows-- as if every nuance of an inter-personal dynamic could suddenly emerge as one grand symptom laying dormant behind a volatile veneer of sympathy. "tell me what's wrong with me." "just tell me what went wrong." and so on.

it is in moments like this that romance is at its absolute worst. desire becomes binary-- tied to a sickly logic that sharpens its fangs on the notion of logic itself. sexless logic. a detective story replaces a romance, only the sleuth is wounded and desperate. during the conversation, we discussed the absurdity of such demands. what if someone were to do it? what if you were literally told what went wrong? can a dynamic between two people (or more) run its course so thoroughly that its end becomes a verbalized utterance? and if so, who in the hell would have the guts to hear it? wishy-washy rejection is bad enough, and yet one feels the masochistic urge to demand of it a slogan.

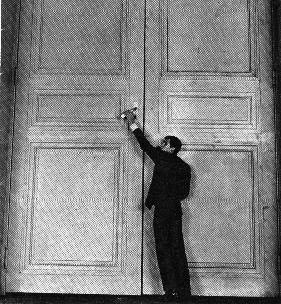

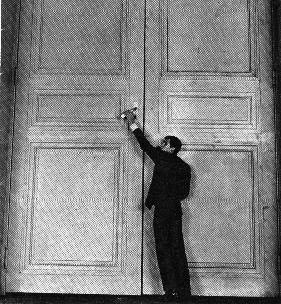

now, kafka is no romantic, but the structure of this pathological momentum becomes the very climate of his work. it sets his thoughts on "a line of escape" as deleuze and guattari might say, but it's a seasick ride along the way. k. asks this very sort of "wrong" question; he builds his universe upon it. those who must enter this world-- meaning those who are uninitiated to it-- have a comic effect, but one that refers back to k. himself. he aspires to greater and greater heights of sublime rejection; to the image of klamm with his head down through a forbidden window.

reading kafka without any over-arching sense of recent rejection (i've been remarkably happy for the past few months), i'm reminded of the absurdity of grand revelations. i find that my world is most engaging when things are neither revealed nor concealed, but apprehended with an affection for the confusion that might oneday emerge. of late, a favorite song of mine is nico's "afraid." a moving, melancholic ballad building up to an effectively melodramatic phrase: you are beautiful and you are alone. when nico sings it, it's sad. but my investment goes beyond that. the sentence could also be a great compliment (to someone or something). it could signal that the obligatory quest for the heart of the matter has ended. it is time to turn your back to the castle, and substitute curiosity for alienation.

as far as my personal inclinations go, like deleuze and guattari, i'm not terribly drawn to either of the two dominant approaches to him-- namely the spiritual and psychoanalytic routes. both have their merits as systems of interpretation, but i don't respond to them personally. the thought of a godless world excites me more than it startles me, and, uh, i guess i get along with my dad pretty well too. while the notion of a "minor" literature-- "to be a sort of stranger within (one's) own language"-- is a fascinating one, i find it less applicable to kafka than d & g might have one believe. "deleuzian" kafka is too covered in "deleuzian" fingerprints to amount to a convincing argument. at times, d & g seem more interested in themselves.

for me, it is through relationships, rather than bureaucracies, that kafka's k. begins to make sense. an example: a few years ago, me and a good friend were both emerging from troubled romantic relationships. sharing a sense of abandonment (or whatever) we began discussing one of the more abject moments of any break-up-- a demand, more or less, to be put on trial. you know the drill... a sense of rejection sets in, and one is filled with an otherworldly desire to know what is wrong with one's self. an embarrassing plea to be told inevitably follows-- as if every nuance of an inter-personal dynamic could suddenly emerge as one grand symptom laying dormant behind a volatile veneer of sympathy. "tell me what's wrong with me." "just tell me what went wrong." and so on.

it is in moments like this that romance is at its absolute worst. desire becomes binary-- tied to a sickly logic that sharpens its fangs on the notion of logic itself. sexless logic. a detective story replaces a romance, only the sleuth is wounded and desperate. during the conversation, we discussed the absurdity of such demands. what if someone were to do it? what if you were literally told what went wrong? can a dynamic between two people (or more) run its course so thoroughly that its end becomes a verbalized utterance? and if so, who in the hell would have the guts to hear it? wishy-washy rejection is bad enough, and yet one feels the masochistic urge to demand of it a slogan.

now, kafka is no romantic, but the structure of this pathological momentum becomes the very climate of his work. it sets his thoughts on "a line of escape" as deleuze and guattari might say, but it's a seasick ride along the way. k. asks this very sort of "wrong" question; he builds his universe upon it. those who must enter this world-- meaning those who are uninitiated to it-- have a comic effect, but one that refers back to k. himself. he aspires to greater and greater heights of sublime rejection; to the image of klamm with his head down through a forbidden window.

reading kafka without any over-arching sense of recent rejection (i've been remarkably happy for the past few months), i'm reminded of the absurdity of grand revelations. i find that my world is most engaging when things are neither revealed nor concealed, but apprehended with an affection for the confusion that might oneday emerge. of late, a favorite song of mine is nico's "afraid." a moving, melancholic ballad building up to an effectively melodramatic phrase: you are beautiful and you are alone. when nico sings it, it's sad. but my investment goes beyond that. the sentence could also be a great compliment (to someone or something). it could signal that the obligatory quest for the heart of the matter has ended. it is time to turn your back to the castle, and substitute curiosity for alienation.

ten good things (california edition)

(...my vacation was totally fantastic...)

10. the window seat, and its quick peeks at that sprawling geo-quilt we call a landscape... the distancing jolt of apprehension and the not-quite-real acknowledgement that you are, indeed, hundreds of feet in the air...

9. a delicious and nostalgic veggie burrito from pokez, with chips and salsa, of course...

8. gabe's house, which is enormous and charming. huge rooms with fancy woodwork (a la west philadelphia) and a pervasive 70's bachelor pad sort of vibe (a la ron burgundy). it offset the near-complete suburbanization of the rest of san diego (ho hum... golden hill is down for the count)...

7. oaxacan food in los angeles with justin and his charming friends, upping the ante on my already-dear love of mexican food. most of my vacations focus on eating and drinking. apologies if you're bored.

6. galleries in chinatown. i know i should feel more ambivalence about the inevitable gentrification that accompanies this phenomenon, but it's just such a cool part of town. emblematic of what i find so charming about LA-- the way everything just sort of butts up against everything else. the scramble keeps me on my toes, i guess. and yes-- i am saying that LA is (occasionally) charming...

5. the desert and the impulse to strip naked and run off into it singing "we are the champions" at the top of my lungs. i feel this way whenever i drive through it, which i had the pleasure of doing en route to berkeley.

4. discovering that erin knows all the words to songs by squeeze. and not just "tempted by the fruit of another" either... she means business.

3. the bay area now exhibition at the yerba buena center for the arts, which was thankfully light on the juxztapoz magazine-type nonsense. i particularly liked josephine taylor's drawings, which combined magic and terror in an evocative way.

2. interacting with strangers without a goddamn computer in front of me (no offense, y'all), and seeing the cartoon wallflower i often paint myself out to be proven (at least partially) false. of course, it helps that i met a wide variety of nice people as well...

1. finishing the trip with a screening of apichatpong weerasethakul's tropical malady, one of the most moving films i've seen all year (and i've seen some doosies)... it merits consideration as the most effectively optimistic movie i've ever seen, exploring the outer limits of desire through courtesy, performative artifice, left-field eroticism and very intense reverence-- all with a mastery deserving a far more detailed post (to say the least). i'll write that one when my jet-lag (sp?) is gone. a pleasurable, thoughtful film to end a pleasurable, thoughtful trip.

george a. romero, land of the dead

i like george romero for many of the same reasons i like sam fuller. both are inventive, intelligent film-makers who give and give and give... their strengths arise out of an affection for genre, a lean and dynamic approach to visual storytelling and a tendency to lay it on thick. they share a wild streak-- an impulse to follow things through to their garish extremes, as well as an eye for the pockets of uncertainty that develop along the way. in the work of both directors, overt gestures have the resonance of covert operations. their films are pinball machines-- and following ninety minutes of spectatorial thrashing, you end up somewhere consistently interesting.

enter land of the dead, and its enjoyably “storybook” origins: forgotten director drifting into obscurity... entertaining, zombie shlock is a surprise hit... hip u.k. director makes artsy fartsy alternative (with mixed results)... some dumb shit makes needless re-make of forgotten director's masterpiece... forgotten director gets budget and resources to show the whole lot of them how it's done.

and on strictly popcorn-crunching terms, romero delivers. no nu-metal, no smart-ass characters you can't wait to see devoured, no "fast zombies," etc. the film rises up from the ashes of the previous three and stands proud. romero revels in gore as well as politics, and has a hell of a good time along the way.

which isn’t to say land doesn’t have its problems. first and foremost, it's simply not long enough. romero has a lot he'd like to say and do, and he doesn’t have enough time to see it all through. for example, there's a nice break in the action about midway through the film, where the central heroic trio are trapped in jail and begin to converse with each other. we get a small taste of the kind of character development that made dawn of the dead so resonant and likeable. asia argento (who, presumably, has been knee-deep in puddles of fake blood since she was old enough to walk) is particularly engaging, and brings a more legitimate toughness to romero's already-nuanced handling of horror femininity. but there isn't enough of her. the characters, though well intended, are painted in broad strokes, and romero spends too much time multi-tasking to give them the love he's proven he can deliver.

painted in equally broad strokes are the political insights, centering mostly around john leguizamo's "cholo"-- a name that is either snarky and clever or shamefully embarrassing (i can’t, personally, decide). cholo, save a few spanish-language profanities, is reduced to a garden-variety "minority"-- an excluded everyman standing in the shadow of white male privilege (personified by a refreshingly understated dennis hopper-- of all people). romero means well, but misses several opportunities to add dimension and complexity to the character.

the finest political moments occur at the peripheries. take for example "charlie," a mentally challenged burn victim who follows the film's protagonist around with an of mice and men-esque homoerotic loyalty. charlie, with his scarred visage and dumb-founded reactions, occupies a strange middle ground between human and zombie. his distorted face is a false alarm in key sequences, further blurring the evaporating lines between self and other. and eugene clark's inverted black protagonist, whose identity as a zombie has been applauded in a number of reviews i've read, is a hell of an interesting move on romero's part. his initial, schlocky zombie moan is romero's grief-stricken battle cry, lamenting how little has changed in america since duane jones was shot that morning after the night of the living dead in 1968.

but the best thing about the film is neither gory and scary nor savvy and political. it is the affection that so obviously went into it, every step of the way. land of the dead enters a landscape of revisionism and profiteering, and says to hell with both. romero makes his movie the way he likes, and does so with with a gleeful generosity that simply won me over. twenty years later, romero's zombie world is as enjoyable as ever, and well worth the wait

enter land of the dead, and its enjoyably “storybook” origins: forgotten director drifting into obscurity... entertaining, zombie shlock is a surprise hit... hip u.k. director makes artsy fartsy alternative (with mixed results)... some dumb shit makes needless re-make of forgotten director's masterpiece... forgotten director gets budget and resources to show the whole lot of them how it's done.

and on strictly popcorn-crunching terms, romero delivers. no nu-metal, no smart-ass characters you can't wait to see devoured, no "fast zombies," etc. the film rises up from the ashes of the previous three and stands proud. romero revels in gore as well as politics, and has a hell of a good time along the way.

which isn’t to say land doesn’t have its problems. first and foremost, it's simply not long enough. romero has a lot he'd like to say and do, and he doesn’t have enough time to see it all through. for example, there's a nice break in the action about midway through the film, where the central heroic trio are trapped in jail and begin to converse with each other. we get a small taste of the kind of character development that made dawn of the dead so resonant and likeable. asia argento (who, presumably, has been knee-deep in puddles of fake blood since she was old enough to walk) is particularly engaging, and brings a more legitimate toughness to romero's already-nuanced handling of horror femininity. but there isn't enough of her. the characters, though well intended, are painted in broad strokes, and romero spends too much time multi-tasking to give them the love he's proven he can deliver.

painted in equally broad strokes are the political insights, centering mostly around john leguizamo's "cholo"-- a name that is either snarky and clever or shamefully embarrassing (i can’t, personally, decide). cholo, save a few spanish-language profanities, is reduced to a garden-variety "minority"-- an excluded everyman standing in the shadow of white male privilege (personified by a refreshingly understated dennis hopper-- of all people). romero means well, but misses several opportunities to add dimension and complexity to the character.

the finest political moments occur at the peripheries. take for example "charlie," a mentally challenged burn victim who follows the film's protagonist around with an of mice and men-esque homoerotic loyalty. charlie, with his scarred visage and dumb-founded reactions, occupies a strange middle ground between human and zombie. his distorted face is a false alarm in key sequences, further blurring the evaporating lines between self and other. and eugene clark's inverted black protagonist, whose identity as a zombie has been applauded in a number of reviews i've read, is a hell of an interesting move on romero's part. his initial, schlocky zombie moan is romero's grief-stricken battle cry, lamenting how little has changed in america since duane jones was shot that morning after the night of the living dead in 1968.

but the best thing about the film is neither gory and scary nor savvy and political. it is the affection that so obviously went into it, every step of the way. land of the dead enters a landscape of revisionism and profiteering, and says to hell with both. romero makes his movie the way he likes, and does so with with a gleeful generosity that simply won me over. twenty years later, romero's zombie world is as enjoyable as ever, and well worth the wait

batman's weird politics

i was fairly excited at the prospect of a grittier batman. i like the darkness of batman, the way he always seems unsure about his own project, etc. and batman begins had all the makings of a more sophisticated superhero flick, which it delivers in heaps with its A-list cast and micro-managed "seriousness." but at the end of the day, it's still a comic book movie. at a certain point it has to split in two: good guy in silly suit vs. bad guy in silly suit. and the ideological process it takes to get there is pretty weird...

****spoilers ahead, and smarmy brain-noodling****

when we begin, young batman is a john walker lindh type-- privileged, pissed off, in a remote location, and involved in shit that's way over his head. he meets terror guru liam neeson, who treats him to the sort of paternalistic physical/psychological training we're used to from kung fu or prison flicks. as neeson's "daddy" status cements into place, we're invited into the trance of his fascist rhetoric. we thrill as batboy's "weakness" pounds its way out of him. we applaud his determination as well as his moral entitlement, and we prepare for a dirty harry-like gutter sweep when he gets back to gotham.

the fascist trance is then interrupted by a moment of ethical clarity. a sudden awareness of something resembling human rights triggers batman to turn on his terrorist clan. he leaves the mystical east confused and "in the right" (according to the movie's spell, at any rate), though it remains unclear how he got there, ideologically. legality, in the new batman universe, keeps changing its mind. batman declares to neeson that he "is not an executioner," and demands the need for trials and sentencing. back in gotham, we get good-cop-bad-cop in the courtroom, and both archetypes, to boot. katie holmes represents liberal idealism, stressing illness and circumstance over retribution. cillian murphy (the film's one cartoonish bad guy) gives form to the inevitable corrupt bureaucracy. his amoral sycophant "scarecrow" (complete with effeminate, euro-hipster fashion sense), slides past holmes' idealism as if he snuck out of a cop flick from the eighties. he marks the comic-book-pinnacle of the movie; where it turns into a cartoon. the goodies and the baddies take their appropriate sides and batman begins as a kinder, guiltier dirty harry.

then things get really weird. neeson (and co.) returns to gotham, now officially "bad" and as the terrorist mastermind of the entire narrative. the same cultish hate-mongering we had so much fun with at the film's beginning takes on al-queda-status from then on out. and what is their weapon of choice? fear itself. fear as chemical warfare-- a fog of psychological vapor, triggering one's worst personal nightmares, spreads across gotham city. if michael moore has suggested (in bowling for columbine, for example) that fear is what orchestrates our violent culture, in batman begins that sentiment is pushed to a topsy-turvy extreme: fear as a weapon of mass destruction. the irrational fear that moore would like to disgard returns as the ammunition of terror itself: destroy the terrorists before they attack us with our fear of them themselves. meta-terror, predicated upon its ability to make itself virial in the abstract, punished (eventually) by a guilt-ridden vigilante.

****spoilers ahead, and smarmy brain-noodling****

when we begin, young batman is a john walker lindh type-- privileged, pissed off, in a remote location, and involved in shit that's way over his head. he meets terror guru liam neeson, who treats him to the sort of paternalistic physical/psychological training we're used to from kung fu or prison flicks. as neeson's "daddy" status cements into place, we're invited into the trance of his fascist rhetoric. we thrill as batboy's "weakness" pounds its way out of him. we applaud his determination as well as his moral entitlement, and we prepare for a dirty harry-like gutter sweep when he gets back to gotham.

the fascist trance is then interrupted by a moment of ethical clarity. a sudden awareness of something resembling human rights triggers batman to turn on his terrorist clan. he leaves the mystical east confused and "in the right" (according to the movie's spell, at any rate), though it remains unclear how he got there, ideologically. legality, in the new batman universe, keeps changing its mind. batman declares to neeson that he "is not an executioner," and demands the need for trials and sentencing. back in gotham, we get good-cop-bad-cop in the courtroom, and both archetypes, to boot. katie holmes represents liberal idealism, stressing illness and circumstance over retribution. cillian murphy (the film's one cartoonish bad guy) gives form to the inevitable corrupt bureaucracy. his amoral sycophant "scarecrow" (complete with effeminate, euro-hipster fashion sense), slides past holmes' idealism as if he snuck out of a cop flick from the eighties. he marks the comic-book-pinnacle of the movie; where it turns into a cartoon. the goodies and the baddies take their appropriate sides and batman begins as a kinder, guiltier dirty harry.

then things get really weird. neeson (and co.) returns to gotham, now officially "bad" and as the terrorist mastermind of the entire narrative. the same cultish hate-mongering we had so much fun with at the film's beginning takes on al-queda-status from then on out. and what is their weapon of choice? fear itself. fear as chemical warfare-- a fog of psychological vapor, triggering one's worst personal nightmares, spreads across gotham city. if michael moore has suggested (in bowling for columbine, for example) that fear is what orchestrates our violent culture, in batman begins that sentiment is pushed to a topsy-turvy extreme: fear as a weapon of mass destruction. the irrational fear that moore would like to disgard returns as the ammunition of terror itself: destroy the terrorists before they attack us with our fear of them themselves. meta-terror, predicated upon its ability to make itself virial in the abstract, punished (eventually) by a guilt-ridden vigilante.

8th street, between walnut and chestnut

by 10:30pm on jeweler's row in philadelphia, the diamond rings and gold chains are locked up for the night. in the store windows, structural terrariums await the coming decor. white felt necks and fingers; hacked and hemmed to the whims of tomorrow's affairs. it remains inviting after hours-- despite its lack of function-- triggering those everyday apocalypse aesthetics... the shopper's void made present... its (obligatory) desiring nothingness... and the icy cool it acquires as a result. all of which had me tuned in, for a moment, walking home tonight.

donald richie, a hundred years of japanese film

donald richie's a hundred years of japanese film is an informative, insightful, and occasionally frustrating read...

informative-- first and foremost-- because richie has been writing about japan (and its films in particular) since the end of world war II, and is perhaps the most influential western thinker concerned with the cinema of the country. accordingly, his accessible and linear account is filled with interesting details. for example, one finds that the earliest silent cinema in japan was traditionally accompanied by a benshi-- a physically present narrarator who's task was to explain what was going on in the on-screen images. in this way (and in several others as well), japanese audiences were introduced to a cinema more directly linked to theatre from the start. richie explores the tensions between film and theatre; how the distinctions generated by such tensions lead to certain sensibilities, and how these sensibilities are interpreted/reconfigured in the west. richie proposes a useful dichotomy between representational film-making (meaning, more or less, the standard of "realism" most typical in the west) and presentational style, which is less rooted in creating a believeable environment, and (in japan, at any rate) builds upon the aesthetic and ideological history of kabuki theatre, bunraku puppetry and things of that sort.

richie is immensely insightful in his ability to distinguish between different approachs to film, and the historical precedents that allow for them. the thesis of the book-- and it is the sort of book that has one-- is that much of japanese film history is built upon the changing nature of japanese identity itself. thus, the concern of many great directors is with a preservation of what it might mean to be japanese in the face of western influence (or eventually--and more specifically-- following WWII and the american occupation). in his anlysis of certain key directors, the dialogue is immensely multi-dimensional. in the work of yasujiro ozu, for example, we see the radicality of his static, understated camerawork alongside the conservative nature of his storylines (and the artistic liberty afforded to him, by the studio system, accordingly). we see the reaction against his style and ideology (in the work of "new wave" figures like nagisa oshima and yasuzo masamura), as well as the eventual return of his influence (in the work of hirokazu kore-eda-- someone i need to see more by-- among others). richie's approach to the films is refreshingly democratic as well. a well-known classic like akira kurosawa's seven samurai occupies essentially the same amount of space as less-hyped wonders like mikio naruse's when a woman ascends the stairs (which is probably my favorite rental-promted-by-the-book thus far).

richie is also frustrating at times, on account of his canonical, modernist inclinations. he remains cheerful enough to the generation following kurosawa, mizoguchi, ozu, etc.-- providing affectionate accounts of the genre subversions of masamura or seijun suzuki, for example. richie likes his art with a capital "A", and thus there is no mention of the pulp samourai films of kenji misumi or the art porn freakouts of koji wakamatsu. which is fair enough, i guess (though, for my money, kurosawa's the hidden fortress isn't any more deep and meaningful than misumi's lone wolf and cub films-- and the latter are waaay more entertaining-- but i digress...). richie's inclinations become more problematic when he arrives at current japanese cinema, wherein the lines between genre, camp, sincerity and innovation become increasingly blurry.

richie is needlessly brutal, for example, to the films of takeshi kitano. kitano, in richie's view, becomes the emblem of assimilated western cool. it's an all too familiar knee-jerk reaction, wherein kitano becomes the eastern equivalent to quentin tarantino. this stereotype-- which drives me crazy-- appears to be predicated exclusively on kitano's taste in suits. first off, tarantino isn't even the right fit for the "strawman" of callous, hateful postmodernism he's made out to be (jackie brown, anyone?)... and certain richie-approved classics like branded to kill are as surface-level hip and flashy as kitano at his coolest... but what's really discouraging is the sense that richie fails to connect at a certain point. his sensibility is too foreign to that of the currently emerging film audience. he can't get past the shoot-outs in kitano to swallow the odd ennui i found so moving in sonatine, for example. his disgust with the idiocy of mainstream culture is so great it prevents him from discovering how the crapola is reconfigured. filmmakers like kitano, kiyoshi kurosawa and (though i'm less thrilled with him personally) even takashi miike, work through the crassness of mainstream culture rather than around it. and they occasionally reach the same heights as those who came before them. but richie puts his blinders on.

still, i emerge from the book a more informed viewer. it's great read, and has happily introduced me to a number of wonderful films/filmmakers, which i will be sure to bore you with posts about in the future.

informative-- first and foremost-- because richie has been writing about japan (and its films in particular) since the end of world war II, and is perhaps the most influential western thinker concerned with the cinema of the country. accordingly, his accessible and linear account is filled with interesting details. for example, one finds that the earliest silent cinema in japan was traditionally accompanied by a benshi-- a physically present narrarator who's task was to explain what was going on in the on-screen images. in this way (and in several others as well), japanese audiences were introduced to a cinema more directly linked to theatre from the start. richie explores the tensions between film and theatre; how the distinctions generated by such tensions lead to certain sensibilities, and how these sensibilities are interpreted/reconfigured in the west. richie proposes a useful dichotomy between representational film-making (meaning, more or less, the standard of "realism" most typical in the west) and presentational style, which is less rooted in creating a believeable environment, and (in japan, at any rate) builds upon the aesthetic and ideological history of kabuki theatre, bunraku puppetry and things of that sort.

richie is immensely insightful in his ability to distinguish between different approachs to film, and the historical precedents that allow for them. the thesis of the book-- and it is the sort of book that has one-- is that much of japanese film history is built upon the changing nature of japanese identity itself. thus, the concern of many great directors is with a preservation of what it might mean to be japanese in the face of western influence (or eventually--and more specifically-- following WWII and the american occupation). in his anlysis of certain key directors, the dialogue is immensely multi-dimensional. in the work of yasujiro ozu, for example, we see the radicality of his static, understated camerawork alongside the conservative nature of his storylines (and the artistic liberty afforded to him, by the studio system, accordingly). we see the reaction against his style and ideology (in the work of "new wave" figures like nagisa oshima and yasuzo masamura), as well as the eventual return of his influence (in the work of hirokazu kore-eda-- someone i need to see more by-- among others). richie's approach to the films is refreshingly democratic as well. a well-known classic like akira kurosawa's seven samurai occupies essentially the same amount of space as less-hyped wonders like mikio naruse's when a woman ascends the stairs (which is probably my favorite rental-promted-by-the-book thus far).

richie is also frustrating at times, on account of his canonical, modernist inclinations. he remains cheerful enough to the generation following kurosawa, mizoguchi, ozu, etc.-- providing affectionate accounts of the genre subversions of masamura or seijun suzuki, for example. richie likes his art with a capital "A", and thus there is no mention of the pulp samourai films of kenji misumi or the art porn freakouts of koji wakamatsu. which is fair enough, i guess (though, for my money, kurosawa's the hidden fortress isn't any more deep and meaningful than misumi's lone wolf and cub films-- and the latter are waaay more entertaining-- but i digress...). richie's inclinations become more problematic when he arrives at current japanese cinema, wherein the lines between genre, camp, sincerity and innovation become increasingly blurry.

richie is needlessly brutal, for example, to the films of takeshi kitano. kitano, in richie's view, becomes the emblem of assimilated western cool. it's an all too familiar knee-jerk reaction, wherein kitano becomes the eastern equivalent to quentin tarantino. this stereotype-- which drives me crazy-- appears to be predicated exclusively on kitano's taste in suits. first off, tarantino isn't even the right fit for the "strawman" of callous, hateful postmodernism he's made out to be (jackie brown, anyone?)... and certain richie-approved classics like branded to kill are as surface-level hip and flashy as kitano at his coolest... but what's really discouraging is the sense that richie fails to connect at a certain point. his sensibility is too foreign to that of the currently emerging film audience. he can't get past the shoot-outs in kitano to swallow the odd ennui i found so moving in sonatine, for example. his disgust with the idiocy of mainstream culture is so great it prevents him from discovering how the crapola is reconfigured. filmmakers like kitano, kiyoshi kurosawa and (though i'm less thrilled with him personally) even takashi miike, work through the crassness of mainstream culture rather than around it. and they occasionally reach the same heights as those who came before them. but richie puts his blinders on.

still, i emerge from the book a more informed viewer. it's great read, and has happily introduced me to a number of wonderful films/filmmakers, which i will be sure to bore you with posts about in the future.

robert frank, cocksucker blues

after years of curiosity, i finally saw robert frank's cocksucker blues. the film documents the rolling stones' 1972 tour for exile on main street, and its heavy emphasis on rock star debauchery (groupie fucking, coke snorting, heroin shooting, etc.) has prevented its release in the years since.

frank's foggy, deliberately incoherent approach wallows in the unglamourous. his camera shows up at every wrong moment-- the point of uncertainty, the aftermath, etc.-- and carves a sleepy portrait of rock excesses as challenging to get through as godard's (more interesting) one plus one. the defiant energy of rock itself is whittled to its spinal remains, leaving only appetite and exhaustion. its music goes unmixed; the performances are reduced to awkward schematics... one of the film's rare spinal tap-style laughs occurs when mick jagger can't find a satisfactory way to sing along with an oblivious stevie wonder, whose performance of "uptight (everything is alright)" involves a swaying head too unpredictable to split the mike with. but frank is less concerned with cheap laughs than with an atmosphere of exhaustion.

as a glimpse into the seedy world of the rolling stones, i found myself a bit disappointed with the film's approach. it amounts to a would-be neutrality-- lots of verite bells and whistles leading one to believe that its pervasive loathsomeness was all there was to engage with. but then i remember the album itself-- how good it sounds, and how inspired the stones seem to have been while making it. concurrently, frank's fatalism seems a bit reactionary. the film gets stuck in his misanthropy. 1972 seems an appropriate year for such sentiments, with nixon in office and the war in vietnam increasingly apocalyptic. and as one of the earliest attempts to, let's say, obliterate the sixties, it's certainly worth a look if you can find a copy.

watching the film in 2005, i considered the history of attacks on sixties ideology (and i'm sure you can name a few yourself), and what they've meant to me. and i'm not sure where to locate myself anymore accordingly. certainly the nihilistic antagonism of punk has been effectively co-opted... is deserving of similiar analytical abuse... and has even received such abuses in whatever form. and certainly i can learn from both attitudes, feeling an affection for hippie warmth one minute and punk angst the next-- all of which has served me well. but ultimately, i must admit to a certain (perhaps sadistic) pre-occupation with the moments where "the sixties" turned sour, in all their artistic forms, and i think that a lot of people feel it with me. i'm less convinced of its inherent radicality at this point, but not entirely convinced that it's useless either. i'm not sure what to do with it...

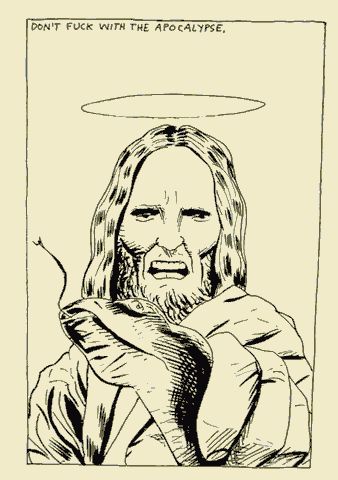

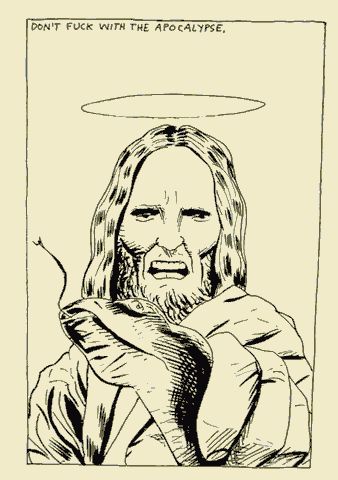

i leave you with raymond pettibon, perhaps the master illustrator of this very predicament...

frank's foggy, deliberately incoherent approach wallows in the unglamourous. his camera shows up at every wrong moment-- the point of uncertainty, the aftermath, etc.-- and carves a sleepy portrait of rock excesses as challenging to get through as godard's (more interesting) one plus one. the defiant energy of rock itself is whittled to its spinal remains, leaving only appetite and exhaustion. its music goes unmixed; the performances are reduced to awkward schematics... one of the film's rare spinal tap-style laughs occurs when mick jagger can't find a satisfactory way to sing along with an oblivious stevie wonder, whose performance of "uptight (everything is alright)" involves a swaying head too unpredictable to split the mike with. but frank is less concerned with cheap laughs than with an atmosphere of exhaustion.

as a glimpse into the seedy world of the rolling stones, i found myself a bit disappointed with the film's approach. it amounts to a would-be neutrality-- lots of verite bells and whistles leading one to believe that its pervasive loathsomeness was all there was to engage with. but then i remember the album itself-- how good it sounds, and how inspired the stones seem to have been while making it. concurrently, frank's fatalism seems a bit reactionary. the film gets stuck in his misanthropy. 1972 seems an appropriate year for such sentiments, with nixon in office and the war in vietnam increasingly apocalyptic. and as one of the earliest attempts to, let's say, obliterate the sixties, it's certainly worth a look if you can find a copy.

watching the film in 2005, i considered the history of attacks on sixties ideology (and i'm sure you can name a few yourself), and what they've meant to me. and i'm not sure where to locate myself anymore accordingly. certainly the nihilistic antagonism of punk has been effectively co-opted... is deserving of similiar analytical abuse... and has even received such abuses in whatever form. and certainly i can learn from both attitudes, feeling an affection for hippie warmth one minute and punk angst the next-- all of which has served me well. but ultimately, i must admit to a certain (perhaps sadistic) pre-occupation with the moments where "the sixties" turned sour, in all their artistic forms, and i think that a lot of people feel it with me. i'm less convinced of its inherent radicality at this point, but not entirely convinced that it's useless either. i'm not sure what to do with it...

i leave you with raymond pettibon, perhaps the master illustrator of this very predicament...